Quiet, part 1

a story of introversion in memes

A while back I heard about the book Quiet by Susan Cain. It’s been on my to-read list on Amazon for at least five years purely because of the subtitle: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking, which struck a chord with me. I feel like that describes my whole life—the quiet one surrounded by non-stop noise.

When I was a child, I could easily play by myself without feeling lonely, though I didn’t do it much. My BFF lived two blocks away and that was when a five-year-old could walk two blocks on a dirt road without fear of being kidnapped. But if my friend wasn’t available, it didn’t bother me to stay home in my own little dreamland.

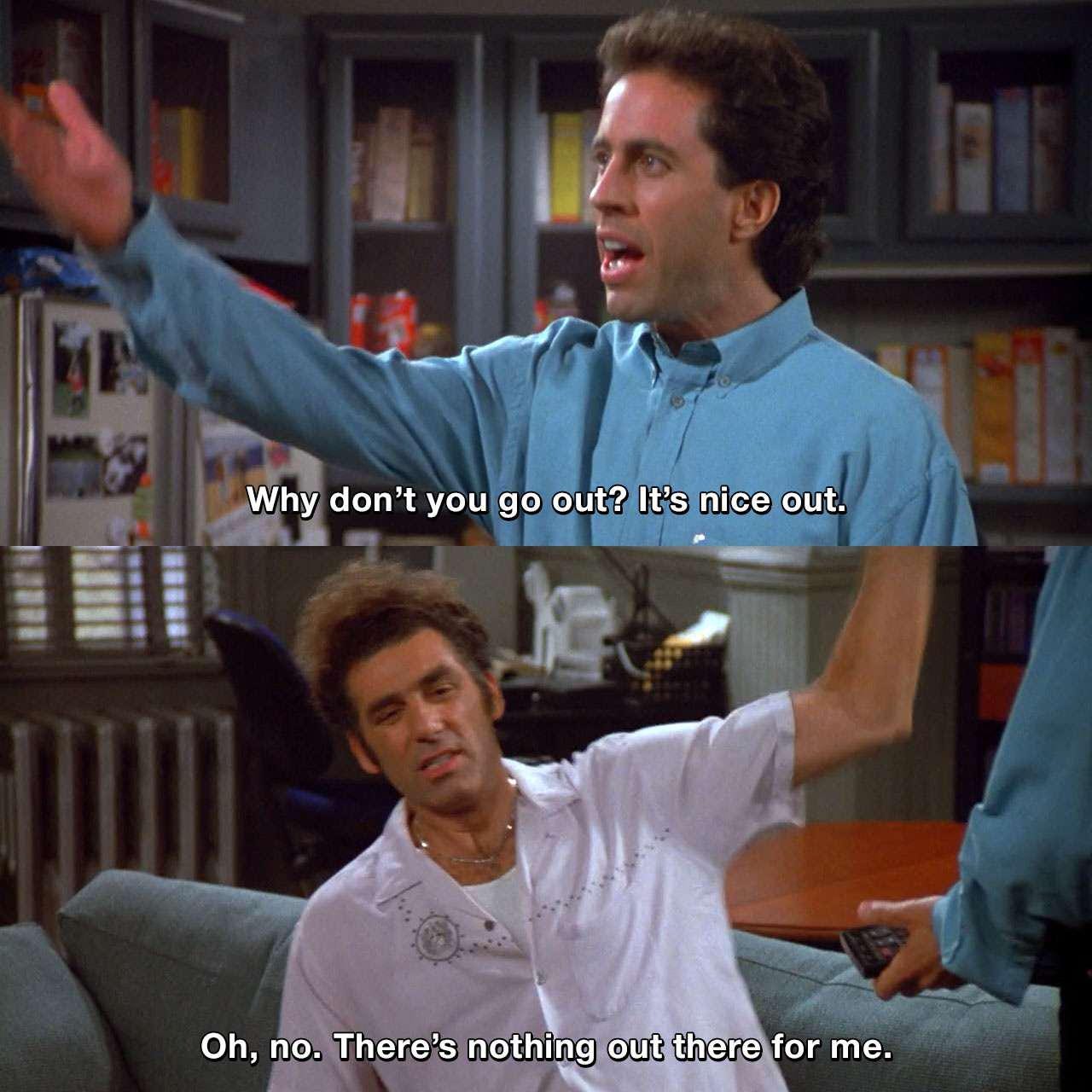

By the time I was a teen, I lived in a small oceanfront town where my friends and I spent our days on the beach and our nights working in the restaurants, serving the thousands of tourists that invaded our little hamlet from Memorial Day until Labor Day. Those days on the beach were, for me, more a time of mental restoration than just hanging out with buddies. I could lie in the sand all day and not say a word, even today.

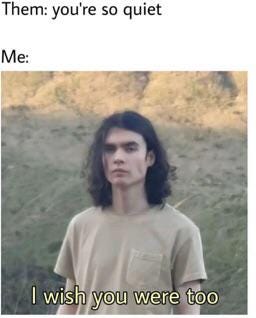

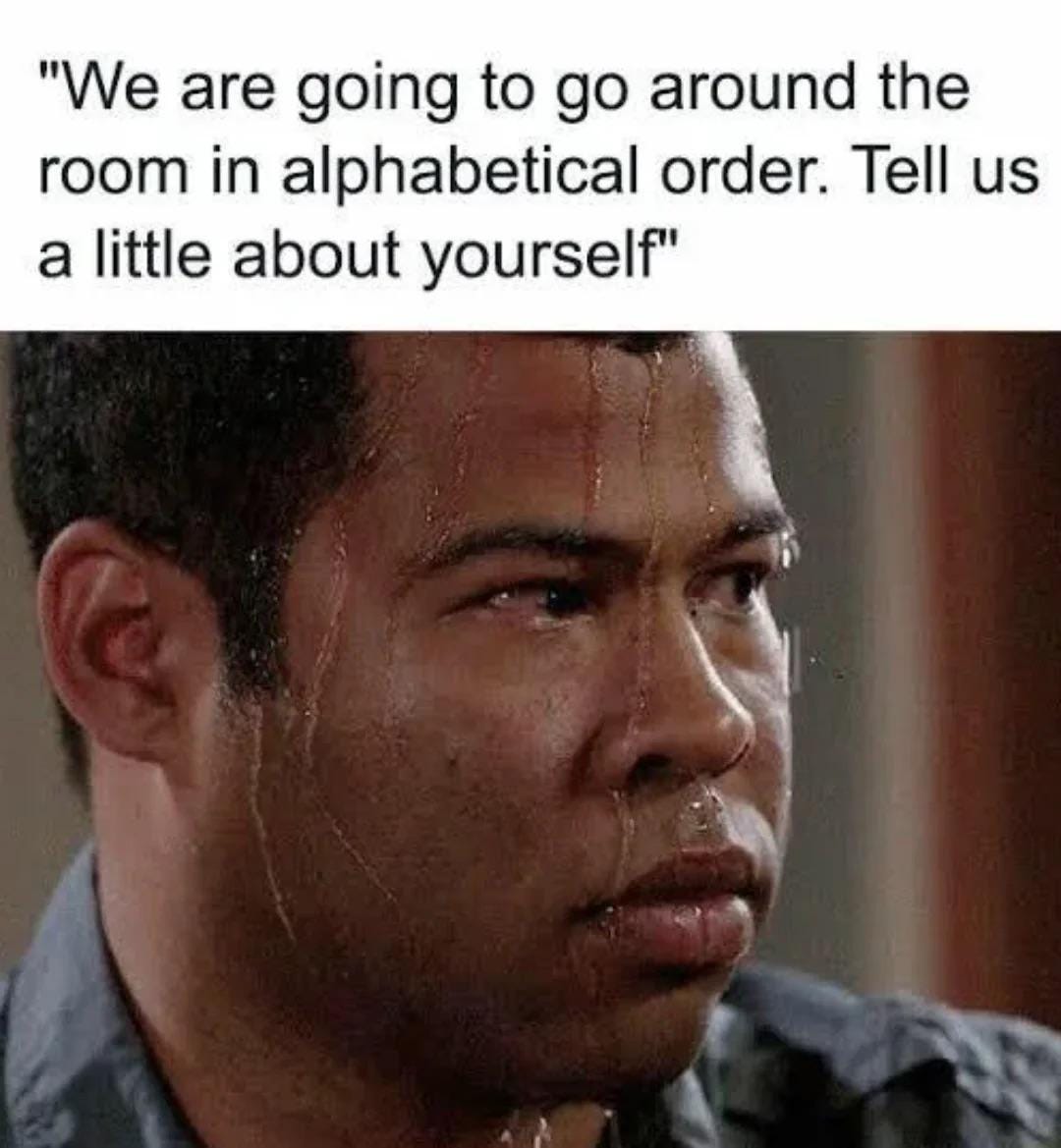

I went off to college not actually understanding what an introvert was, but knowing deep in my soul that I was not the outgoing, talkative type. I detested “mixers” and having to make small talk. The first-day-of-class-go-around-the-room-and-tell-us-who-you-are ritual was torture.

Then I married a man who is the complete opposite of me, 100% extrovert who would always do all the talking for both of us and I thought I’d come up with the perfect solution. I could hide behind all his words and never have to come up with my own. It sounded heavenly back then but it turned out to not be very healthy.

That’s not the way it works in real life. After decades of him doing all the talking and me doing none, I began to feel not only hidden but almost squashed, even though I was the one who’d chosen to be squashed. I started thinking of all the things I wanted to say but didn’t (again, my choice).

So I started a blog back when they were a new thing. It was mostly just daily drivel, nothing heavy or deep. I wrote for the satisfaction of getting thoughts out of my person and into the world, but from the safety of an unseen keyboard. By this time I was knee-deep in homeschooling five children and moving every five or seven years as a military spouse, and I only half-heartedly kept up with the stream of nonsense I posted on blogspot. I loved this because I could write when I wanted to and there was no pressure to keep up a schedule of communication. I wasn’t being timed or judged. I got to “hang out” with other homeschooling moms and share our daily wins and losses.

Then for reasons since forgotten, I walked away from it. As far as the internet knew, I ceased to exist until many years later when I came back as Beyond Momlife on WordPress, which within two years disappeared into the ether one day. Poof. Words gone. Something about the webhost sending me renewal emails that I never got. I vowed I was done and crawled back in my hole.

Then came The Accident in 2018 and so much changed in my life. That was the period in which I thought I was crazy, losing it, (insert all the mental health pseudo-terms) and eventually started therapy, which was great but also began to uncover a lot of other unlovely stuff that had happened through my life and which I unsuccessfully tried to bury without acknowledging but basically exploded into my life whether I wanted it to or not.

I had no choice but to start dealing with my issues and their root causes, and that is what has sent me down the intersection-of-faith-and-psychology rabbit hole. It’s a whole thing. And here we are, reading the book Quiet.

Mostly my studies in the last seven years have all been focused on the question I asked a zillion times: What is wrong with me? And while I still don’t have one definitive answer, I can say what I’ve learned is that mostly there is nothing wrong with me, as I have thought literally since childhood. I am a normal human experiencing normal human things. My issues are that I have tried to be who I am not for myriad unhealthy reasons, and it hasn’t worked out too well. I firmly believe that every high school senior should spend a year in therapy. It would have helped me so much back then.

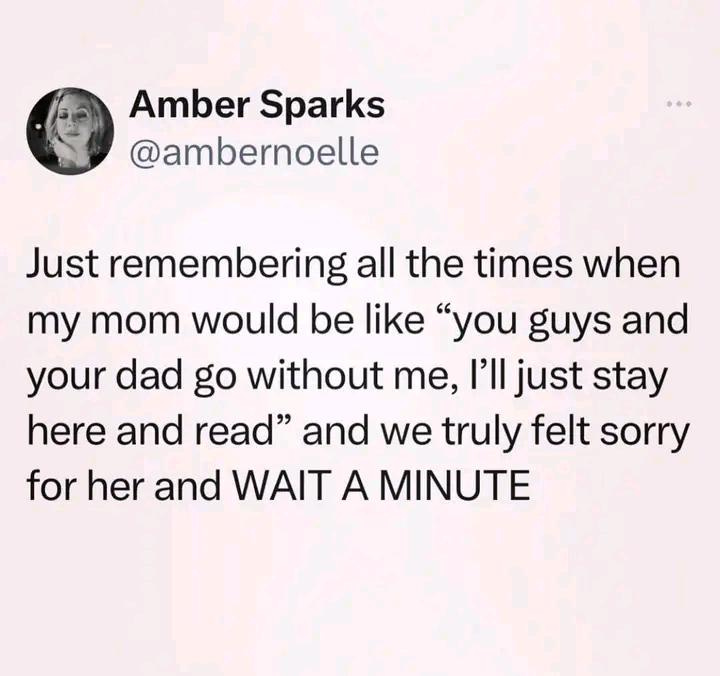

I have pretty much always felt that I am an introvert, even when I didn’t know the word for it. That doesn’t mean I always want to stay home, holed up in my bedroom with a book—although that is an attractive option sometimes. I love being with people as long as I’m not being pressured to be fake.

But the subtitle of this book was what drew me: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking.

The Power of Introverts . . .

Haven’t we all learned that the extroverts are the ones who have all the power? Aren’t we told that introverts should come out of their shells, as if there is something wrong with us? What power could we possibly have?

The author spends the first part of the book describing her experiences at Harvard Business School (you don’t get in unless you’re an extrovert) and a Tony Robbins event (I can’t imagine surviving this). She tells about HBS requiring leaders to make quick decisions, even if they’re wrong, and that is an introvert’s nightmare (she explains why later in the book). Early chapter titles include “How Extroversion Became the Cultural Ideal” and “The Myth of Charismatic Leadership.”

Then she dives into the biology of personality, which is what really fascinated me. Actual brain structures and chemicals. Did you know introverts and extroverts process dopamine differently? Extroverts are typically much more reward-sensitive, chasing the “feeling” of achievement. When an extrovert tells you about some great thing she is going to do in the future, she is already experiencing the hit of dopamine as a reward for something she hasn’t even accomplished yet.

Extroverts don’t really want to hear from people with opposing views. Cain says, “If you focus on achieving your goals, as reward-sensitive extroverts do, you don’t want anything to get in your way . . . You speed up in an attempt to knock these roadblocks down.”1 They have sort of a “damn the torpedoes; full speed ahead!” approach to life. Don’t bog me down me with details.

She goes on, “Introverts, in contrast, are constitutionally programmed to downplay reward . . . and scan for problems.”

“As soon as they [introverts] get excited, they’ll put the brakes on and think about peripheral issues that may be more important.”2 She describes this as “a hedge against risk.”3

I’ll try to grossly oversimplify the book’s explanation of why this is.

We all have an “old brain” and a “new brain.” The old brain is the limbic system, which is “emotional and instinctive” and is “sometimes called the brain’s pleasure center.”4 Its job is to get excited and say, “Yes! Let’s do this new thing! It will be fun!”

The new brain is the neocortex, which is “responsible for thinking, planning, language, and decision-making.”5 Its job is to say, “Hold on a minute. There could be danger here, there are unknowns, and we haven’t evaluated the risks yet!”

In a nutshell, Ms. Cain theorizes, the tendency to be controlled by the old brain is what makes you an extrovert. The tendency to listen to the new brain is what makes you an introvert.

Maybe this doesn’t matter one bit to you, but for me, it is validating. I have spent my adult life married to an extroverted visionary who always wants to do the next big thing, whatever it is. And I have always been the person who slams on the brakes and thinks of everything that could go wrong. I what-if every idea to death and want to examine all the angles. Our extrovert culture calls this being a “killjoy,” and I have absorbed that conclusion with all the guilt and shame associated with it. And the broad conservative Christian culture shames wives who “aren’t supportive,” who don’t immediately jump on board every crazy idea because their brains are wired to evaluate risk first.

Now I know that I am not actually a killjoy. I am a cautious considerer, just like my daddy was, because it is wired in my brain that way. I came from the womb with this bent toward higher sensitivity to risk, just as my husband was born with his bent to charge over every hill without knowing what was on the other side.

I am sure God gave me and my husband to each other specifically because of our extreme oppositeness. I needed a little spark to move and he needed some whoa-there.

I have much more to share about being quiet—namely, what does God say about it?—but since I’m already over 1600 words, I’ll continue next week with part 2. Stay tuned.

Cain, Susan. Quiet. p. 166.

Ibid. p. 167.

Ibid. p. 167.

Ibid. p. 158.

Ibid. p. 159.

Your next read needs to be The Powerful Purpose of Introverts: Why the World Needs YOU to BE YOU by Holley Gerth. It's so good!!

Thank you, Karen. I enjoyed reading your article. My oldest son is very quiet. I have often told him he could be a politician because he is very good about not answering a direct question. I shared your article with him to see what his thoughts about it might be.

I am an extrovert just over the introvert/extrovert border line living with a household of introverts of various degrees. Which at present is just my husband as the rest have flown the nest.

Looking forward to part two and wondering how you approach your visionary husband’s ideas with your cautious risk adverse/assessment response.